ROCKEFELLER NOW PLANS TO ORGANISE OIL MARKETING AS HE HAD ALREADY ORGANISED OIL TRANSPORTING AND REFINING — WONDERFULLY EFFICIENT AND ECONOMICAL SYSTEM INSTALLED — CURIOUS PRACTICES INTRODUCED — REPORTS OF COMPETITORS' BUSINESS SECURED FROM RAILWAY AGENTS — COMPETITORS' CLERKS SOMETIMES SECURED AS ALLIES — IN MANY INSTANCES FULL RECORDS OF ALL OIL SHIPPED ARE GIVEN STANDARD BY RAILWAY AND STEAMSHIP COMPANIES — THIS INFORMATION IS USED BY STANDARD TO FIGHT COMPETITORS — COMPETITORS DRIVEN OUT BY UNDERSELLING — EVIDENCE FROM ALL OVER THE COUNTRY — PRETENDED INDEPENDENT OIL COMPANIES STARTED BY THE STANDARD — STANDARD'S EXPLANATION OF THESE PRACTICES IS NOT SATISFACTORY — PUBLIC DERIVES NO BENEFIT FROM TEMPORARY LOWERING OF PRICES — PRICES MADE ABNORMALLY HIGH WHEN COMPETITION IS DESTROYED

TO know every detail of the oil trade, to be able to reach at any moment its remotest point, to control even its weakest factor — this was John D. Rockefeller's ideal of doing business. It seemed to be an intellectual necessity for him to be able to direct the course of any particular gallon of oil from the moment it gushed from the earth until it went into the lamp of a housewife. There must be nothing — nothing in his great machine he did not know to be working right. It was to complete this ideal, to satisfy this necessity, that he undertook, late in the seventies, to organise the oil markets of the world, as he had already organised oil refining and oil transporting. Mr. Rockefeller was driven to this new task of organisation not only by his own curious intellect; he was driven to it by that thing so abhorrent to his mind — competition. If, as he claimed, the oil business belonged to him, and if, as he had announced, he was prepared to refine all the oil that men would consume, it followed as a corollary that the markets of the world belonged to him. In spite of his bold pretensions and his perfect organisation, a few obstinate oil refiners still lived and persisted in doing business. They were a fly in his ointment — a stick in his wonderful wheel. He must get them out; otherwise the Great Purpose would be unrealised. And so, while engaged in organising the world's markets, he incidentally carried on a campaign against those who dared intrude there.

When Mr. Rockefeller began to gather the oil markets into his hands he had a task whose field was literally the world, for already, in 1871, the year before he first appeared as an important factor in the oil trade, refined oil was going into every civilised country of the globe. Of the five and a half million barrels of crude oil produced that year, the world used five millions, over three and a half of which went to foreign lands. This was the market which had been built up in the first ten years of business by the men who had developed the oil territory and invented the processes of refining and transporting, and this was the market, still further developed, of course, that Mr. Rockefeller inherited when he succeeded in corralling the refining and transporting of oil. It was this market he proceeded to organise.

The process of organisation seems to have been natural and highly intelligent. The entire country was buying refined oil for illumination. Many refiners had their own agents out looking for markets; others sold to wholesale dealers, or jobbers, who placed trade with local dealers, usually grocers. Mr. Rockefeller's business was to replace independent agents and jobbers by his own employees. The United States was mapped out and agents appointed over these great divisions. Thus, a certain portion of the Southwest — including Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas and Texas — the Waters-Pierce Oil Company, of St. Louis, Missouri, had charge of; a portion of the South — including Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi — Chess, Carley and Company, of Louisville, Kentucky, had charge of. These companies in turn divided their territory into sections, and put the subdivisions in the charge of local agents. These local agents had stations where oil was received and stored, and from which they and their salesmen carried on their campaigns. This system, inaugurated in the seventies, has been developed until now the Standard Oil Company of each state has its own marketing department, whose territory is divided and watched over in the above fashion. The entire oil-buying territory of the country is thus covered by local agents reporting to division headquarters. These report in turn to the head of the state marketing department, and his reports go to the general marketing headquarters in New York.

To those who know anything of the way in which Mr. Rockefeller does business, it will go without saying that this marketing department was conducted from the start with the greatest efficiency and economy. Its aim was to make every local station as nearly perfect in its service as it could be. The buyer must receive his oil promptly, in good condition, and of the grade he desired. If a customer complained, the case received prompt attention and the cause was found and corrected. He did not only receive oil; he could have proper lamps and wicks and burners, and directions about using them.

The local stations from which the dealer is served to-day are models of their kind, and one can easily believe they have always been so. Oil, even refined, is a difficult thing to handle without much disagreeable odour and stain, but the local stations of the Standard Oil Company, like its refineries, are kept orderly and clean by a rigid system of inspection. Every two or three months an inspector goes through each station and reports to headquarters on a multitude of details — whether barrels are properly bunged, filled, stencilled, painted, glued; whether tank wagons, buckets, faucets, pipes, are leaking; whether the glue trough is clean, the ground around the tanks dry, the locks in good condition; the horses properly cared for; the weeds cut in the yard. The time the agent gets around in the morning and the time he takes for lunch are reported. The prices he pays for feed for his horses, for coal, for repairs, are noted. In fact, the condition of every local station, at any given period, can be accurately known at marketing headquarters, if desired. All of this tends, of course, to the greatest economy and efficiency in the local agents.

But the Standard Oil agents were not sent into a territory back in the seventies simply to sell all the oil they could by efficient service and aggressive pushing; they were sent there to sell all the oil that was bought. "The coal-oil business belongs to us," was Mr. Rockefeller's motto, and from the beginning of his campaign in the markets his agents accepted and acted on that principle. If a dealer bought but a barrel of oil a year, it must be from Mr. Rockefeller. This ambition made it necessary that the agents have accurate knowledge of all outside transactions in oil, however small, made in their field. How was this possible? The South Improvement scheme provided perfectly for this, for it bound the railroad to send daily to the principal office of the company reports of all oil shipped, the name of shipper, the quantity and kind of oil, the name of consignee, with the destination and the cost of freight. [91] Having such knowledge as this, an agent could immediately locate each shipment of the independent refiner, and take the proper steps to secure the trade. But the South Improvement scheme never went into operation. It remained only as a beautiful ideal, to be worked out as time and opportunity permitted. The exact process by which this was done it is impossible to trace. The work was delicate and involved operations of which it was wise for the operator to say nothing. It is only certain that little by little a secret bureau for securing information was built up until it is a fact that information concerning the business of his competitors, almost as full as that which Mr. Rockefeller hoped to get when he signed the South Improvement Company contracts, is his to-day. Probably the best way to get an idea of how Mr. Rockefeller built up this department, as well as others of his marketing bureau, is to examine it as it stands to-day. First, then, as to the methods of securing information which are in operation.

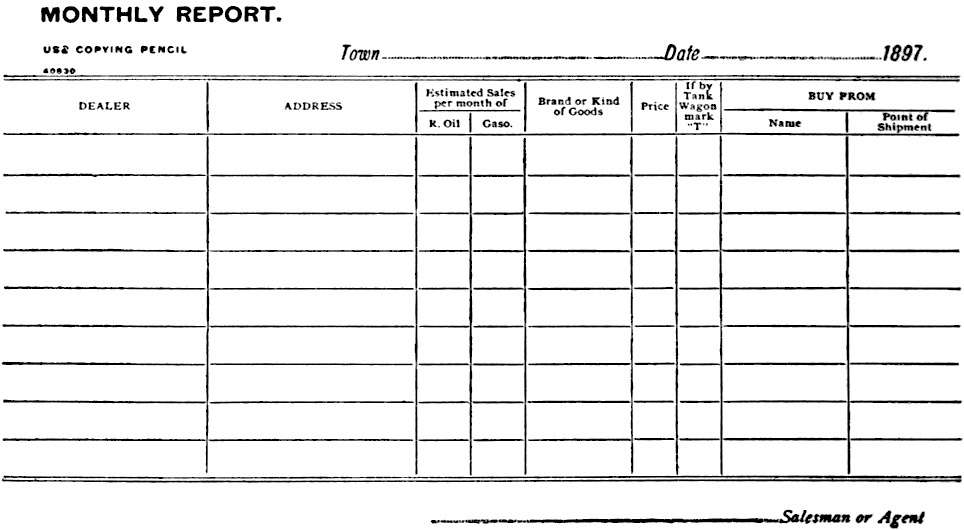

Naturally and properly the local agents of the Standard Oil Company are watchful of the condition of competition in their districts, and naturally and properly they report what they learn. "We ask our salesmen and our agents to keep their eyes open and keep us informed of the situation in their respective fields," a Standard agent told the Industrial Commission in 1898. "We ask our agents, as they visit the trade, to make reports to us of whom the different parties are buying; principally to know whether our agents are attending to their business or not. If they are letting too much business get away from them, it looks as if they were not attending to their business. They get it from what they see as they go around selling goods." But there is no such generality about this part of the agent's or salesman's business as this statement would lead one to believe. As a matter of fact it is a thoroughly scientific operation. The gentleman who made the above statement, for instance, sends his local agents a blank like the following to be made out each month:

EXHIBIT "B—R" [92]

The local agent gets the information to fill out such a report in various ways. He questions the dealers closely. He watches the railway freight stations. He interviews everybody in any way connected with the handling of oil in his territory. All of which may be proper enough. When, in the early eighties, Howard Page, of the Standard Oil Company, was in charge of the Standard shipping department in Kentucky, his agents visited the depots once a day to see what oil arrived there from independent shippers. A record of these shipments was made and reported monthly to Mr. Page. He was able to tell the Interstate Commerce Commission, in 1887, almost exactly what his rivals had been shipping by rail and by river. Mr. Page claimed that his agents had no special privileges; that anybody's agents would have been allowed to examine the incoming cars, note the consignor, contents and consignee. It did not appear in the examination, however, that anybody but Mr. Page had sent agents to do such a thing. The Waters-Pierce Oil Company, of St. Louis, once paid one of its Texas agents this unique compliment: "We are glad to know you are on such good terms with the railroad people that Mr. Clem (an agent handling independent oil) gains nothing by marking his shipments by numbers instead of names." In the same letter the writer said: "Would be glad to have you advise us when Clem's first two tanks have been emptied and returned, also the second two to which you refer as having been in the yard nine and sixteen days, that we may know how long they have been held in Dallas. The movement of tank cars enters into the cost of oil, so it is necessary to have this information that we may know what we are competing with." [93]

|

Table of Contents |  |